Last week, I wrote about the importance of input validation for the security, appearance, and performance of your application. An astute reader commented that we should think about output validation as well. I love it when people give me ideas for blog posts!

There are three main things to think about when testing outputs:

1. How is the output displayed?

A perfect example of an output that you would want to check the appearance of is a phone number. Hopefully when a user adds a phone number to your application’s data store it is being saved without any parentheses, periods, or dashes. But when you display that number to the user, you probably won’t want to display it as 8008675309, because that’s hard to read. You’ll want the number to be formatted in a way that the user would expect; for US users, the number would be displayed as 800-867-5309 or (800) 867-5309.

Another example would be a currency value. If financial calculations are made and the result is displayed to the user, you wouldn’t want the result displayed as $45.655, because no one makes payments in half-pennies. The calculation should be rounded or truncated so that there are only two decimal places.

2. Will the result of a calculation be saved correctly in the database?

Imagine that you have an application that takes a value for x and a value for y from the user, adds them together, and stores them as z. The data type for x, y, and z is set to tinyint in the database. If you’re doing a calculation with small numbers, such as when x is 10 and y is 20, this won’t be a problem. But what happens if x is 255- the upper limit of tinyint- and y is 1? Now your calculated value for z is 256, which is more than can be stored in the tinyint field, and you will get a server error.

Similarly, you’ll want to make sure that your calculation results don’t go below zero in certain situations, such as an e-commerce app. If your user has merchandise totaling $20, and a discount coupon for $25, you don’t want to have your calculations show that you owe them $5!

3. Are the values being calculated correctly?

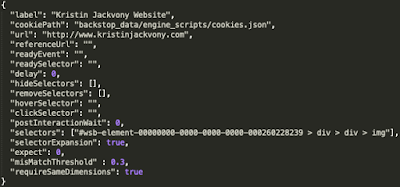

This is especially important for complicated financial applications. Let’s imagine that we are testing a tax application for the Republic of Jackvonia. The Jackvonia tax brackets are simple:

There is only one type of tax deduction in Jackvonia, and that is the dependents deduction:

The online tax calculator for Jackvonia residents has an income field, which can contain any dollar amount from 0 to one million dollars; and a dependents field, which can contain any whole number of dependents from 0 to 10. The user enters those values and clicks the “Calculate” button, and then the amount of taxes owed appears.

If you were charged with testing the tax calculator, how would you test it? Here’s what I would do:

First, I would verify that a person with $0 income and 0 dependents would owe $0 in taxes.

Next, I would verify that it was not possible to owe a negative amount of taxes: if, for example, a person made $25,000 and had three dependents, they should owe $0 in taxes, not -$50.

Then I would verify that the tax rate was being applied correctly at the boundaries of each tax bracket. So a person who made $1 and had 0 dependents should owe $.01, and a person who made $25,000 and had 0 dependents should owe $250. Similarly, a person who made $25,001 and had 0 dependents should owe $750.03 in taxes. I would continue that pattern through the other tax brackets, and would include a test with one million dollars, which is the upper limit of the income field.

Finally, I would test the dependents calculation. I would test with 1, 2, and 3 dependents in each tax bracket and verify that the $100, $200, or $300 tax deduction was being applied correctly. I would also do a test with 4, 5, and 10 dependents to make sure that the deduction was $300 in each case.

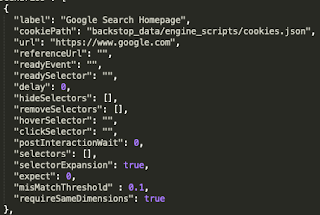

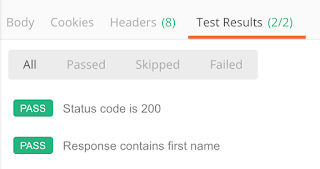

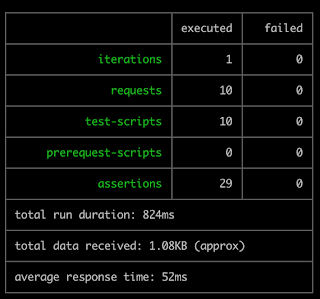

This is a lot of repetitive testing, so it would definitely be a good idea to automate it. Most automation frameworks allow a test to process a grid or table of data, so you could easily test all of the above scenarios and even add more for more thorough testing.

Output validation is so important because if your users can’t trust your calculations, they won’t use your application! Remember to always begin with thinking about what you should test, and then design automation that verifies the correct functionality even in boundary cases.