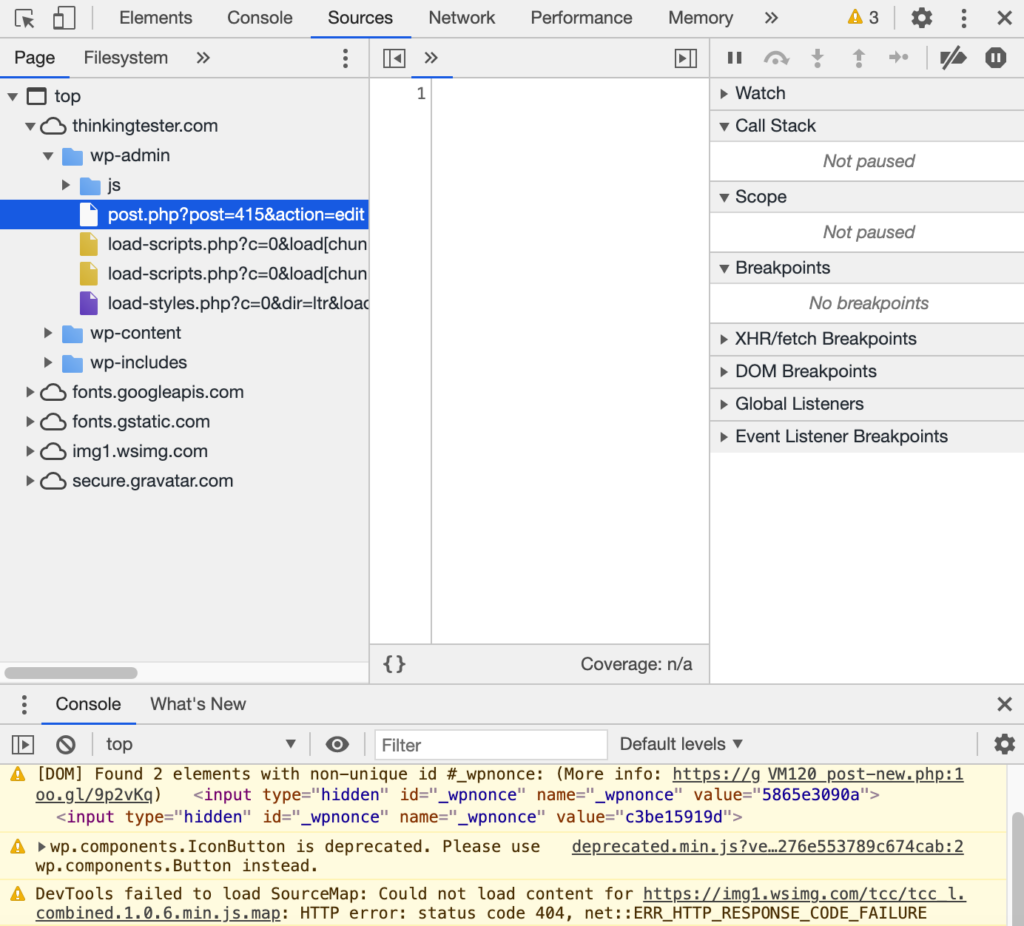

Recently, I took this great course on Locating Web Elements from Andrew Knight, through Test Automation University. In addition to learning helpful syntaxes for accessing elements, I also learned about yet another way we can use DevTools to help us!

One of the most annoying things about UI test automation is trying to figure out how to locate an element on a page if it doesn’t have an automation id. You are probably aware that if you open the Developer Tools in Chrome, you can right-click on an element on a Web page, select “Inspect” and the element will be highlighted in the DOM. This is useful, but there’s something even more useful hidden here: there’s a search bar that allows you to see if the locator you are planning to use in your test will work as you are expecting. Let’s walk through an example of how to use this valuable tool.

Let’s navigate to this page, which is part of Dave Haeffner’s “Welcome to the Internet” site, where you can practice finding web elements. On the Challenging DOM page, there’s a table with hard-to-find elements. We’re going to try locating the table element with the text “Iuvaret4”.

First, we’ll open DevTools. The easiest way to do this is to right-click on one of the elements on the page and choose “Inspect”. The Dev Tools will open either on the right or bottom of the page, and the Elements section will be displaying the DOM.

Now, we’ll open the search bar. Click somewhere in the Elements section, then click Ctrl-F. The search bar will open below the elements section, and the search bar will say “Find by string, selector, or XPath”.

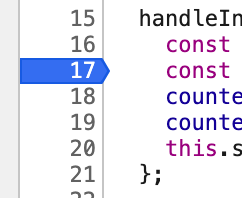

We’ll use this tool to find the “Iuvaret4” element with css. Right-click on the “Iuvaret4” element in the table, and choose “Inspect”. The element will be highlighted in the DOM. Looking at the DOM, we can see that this is a <td> (table data) element, which is part of a <tr> (table row) element. So let’s see what happens if we put tr in the search bar and click Enter. It returns 13 elements. You can click the up and down arrows at the side of the search bar to highlight each element found. The first “tr” the search returns is just part of the word “demonstrates”. The next “tr” is part of the table head. The following “tr”s are part of the table body, and this is where our element is. So let’s put tbody tr in the search bar and click Enter. Now we’ve narrowed our search down to 10 results, which are the rows of the table body.

We know that we want the 5th row in the table body, so now let’s search for tbody tr:nth-child(5). This search narrows things down to the row we want. Now we can look for the <td> element we want. It’s the first element in the row, so if we search for tbody tr:nth-child(5) td:nth-child(1) we will narrow the search down to the exactly the element we want.

This is a pretty good CSS selector, but let’s see if we can make it shorter! Try removing the “tbody” from the search. It turns out the element can be located just fine by simply using tr:nth-child(5) td:nth-child(1).

Now we have a good way to find the element we want with CSS, but what happens if a new row is added to the table, or if the rows are in random order? As soon as the rows change we will be locating the wrong element. It would be better if we could search for a specific text. CSS doesn’t let us do this, so let’s try to find our element with XPath.

Remove the items in the search bar and let’s start by searching on the table body. Put //tbody in the search field and click Enter. You can see when you hover over the highlighted section in the DOM that the entire table body is highlighted on the page.

Inside the table body is the row with the element we want, so we’ll now search for //tbody/tr. This gives us ten results; the ten rows of the table body.

We know that we want to select a particular <td> element in the table body: the element that contains “Iuvaret4”. So we’ll try searching for this: //tbody/tr/td[contains(text(), “Iuavaret4”)]. We get the exact result we want, so we’ve got an XPath expression we can use.

But as with our CSS selector, it might be possible to make it shorter. Try removing the “tbody” and “tr” from the selection. It looks like all we need for our XPath is //td[contains(text(), “Iuvaret4”)].

Without this helpful search tool, we would be trying different CSS and XPath combinations in our test code and running our tests over and over again to see what worked. This Dev Tools feature lets us experiment with different locator strategies and get instant results!